Mosquito Season

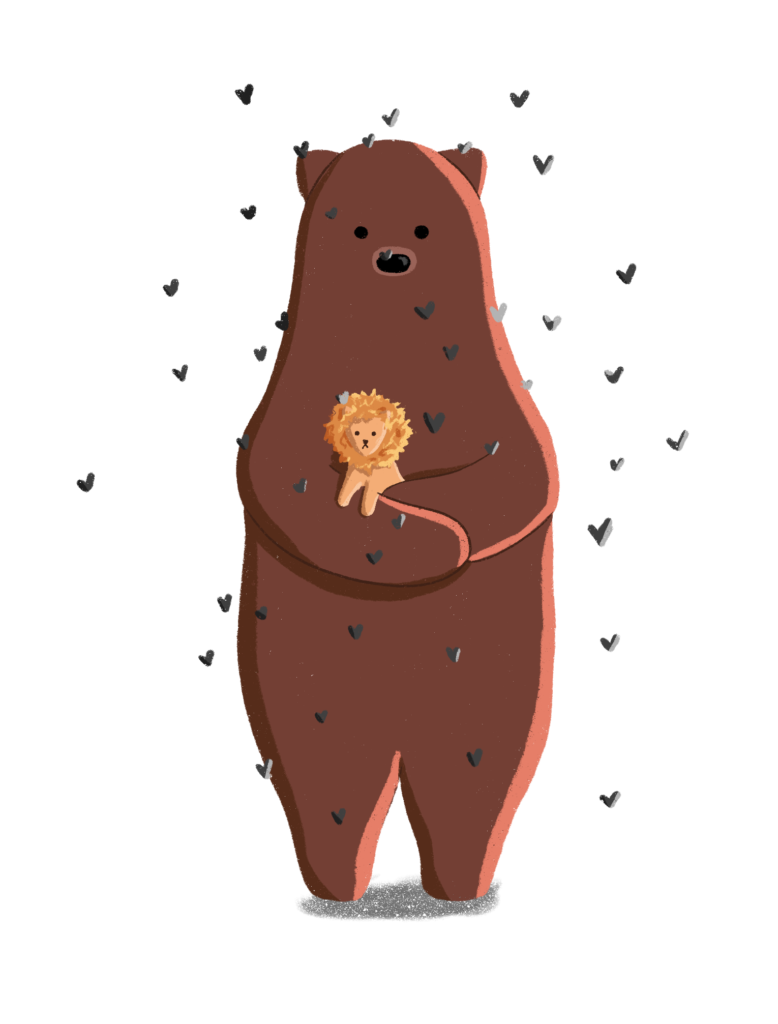

No matter what month it is, no matter what time of day, when Collin leaves the house it is mosquito season.

Today is no different.

One by one the mosquitos delicately land on Collin.

Crawling on and biting into his body, the small and subtle movements are not enough for Collin to be certain that it’s something other than his skin or fur.

Mosquitos are the kind of creatures where, unless there are many of them, their presence is not felt until long after they’ve gone.

Besides, the outside world is way too chaotic for him to notice.

But just because he can’t notice them, doesn’t mean he still can’t be affected by them.

Everything he does seems to be a little harder but he can’t understand why.

Feeling uncomfortable, without an obvious cause, Collin blames it on himself rather than an outside force.

It’s not until he’s back home that he begins to question whether it truly was his own body making that sensation.

There are small marks that are left. Collin itches desperately to get the sensation off of his body.

Sometimes there is no mark, just the itchy feeling left on his body. Collin cannot be certain why or how his skin got so itchy.

The phase of the moon is waxing tonight, thank goodness. A favourable time to be bitten. Collin’s head is a lot clearer so he knows how to care for himself properly.

When the moon is waning it is a much different story. At these times, the most sensible coping method becomes a meltdown. Even if a simple mosquito bite is the only cause.

But it isn’t just a simple mosquito bite.

Weighing just 2.5 milligrams, you’d be forgiven for thinking they were harmless creatures.

Being the deadliest animals on the planet, mosquitos are not taken particularly seriously.

Yet, for being the deadliest animal on earth, a meltdown seems like the more appropriate reaction. But alas, it is not treated as such.

A bear afraid of a mosquito?! How embarrassingly shameful.

Not Having Empathy for Empathy

Thanks to the theory of mind (ToM) research conducted by Simon Baron-Cohen in 1985, it is widely believed that autistic people lack empathy.

While there are many autistics who are hyposensitive (who experience decreased sensitivity) as opposed to hypersensitive (increased sensitivity), hypersensitive autistics can often appear hyposensitive due to something called alexithymia – the inability to recognise/identify one’s own emotions and/or feelings unless they are extremely intense.

This does not mean that they are unempathetic. Baron-Cohen’s ToM research inadvertently tells you more about a concept known as ‘double empathy’. Double empathy is a theory that suggests that empathy is not a one-way street, as previously believed. The Baron-Cohen’s claim that autistics don’t feel empathy comes directly from a non-empathetic place, making the claim completely ironic.

In other words, it becomes hard for someone to see someone else as empathetic if one is not empathetic themselves.

If many autistics struggle to recognise their own emotions you can imagine how much turmoil and confusion is created when someone else’s emotions are added to the mix.

The cynics amongst you may think, if you can’t feel your own emotions you can’t possibly feel someone else’s. I, and many other autistics, beg to differ.

It’s been extremely difficult putting my empathetic experience into words, but here is what I have come up with thus far.

In my experience, when it comes to empathising with others there are two ways I can connect; intuitively and intellectually.

I relate a lot more to these terms than cognitive and affective empathy because I find I got progressively more confused the more I tried to understand them, their differences and where I sit with my experiences. So for now, I will stick with intuitive and intellectual as terms.

I have a long history with intellectualising things which I will explore in more detail next post. But in short, intellectualising is my main way of understanding the world around me, especially emotions. In todays post I want to focus on intuitive empathy.

Mainly because it is extremely hard for me to intellectualise something that is inherently intuitive.

Like Collin I struggle with the subtleties in the moment. Just because I struggle to notice it, does not mean that it isn’t there. Reflecting (intellectualising) is where I understand. But reflecting can just as easily work against me.

I’ve spent many years internalising my empathy, convincing myself that these feelings were my own and I was the one doing the projecting. I convinced myself that no one else felt what I was feeling, yet, I didn’t even know what I was feeling or where it came from. The feelings – whatever they were – would disappear almost the second I left that situation only to be replaced by total exhaustion.

Being exhausted and empty after every social interaction I began to wonder if maybe these feelings weren’t my own. To be honest, I still don’t know. This has actually been my hardest post to write so far as I keep going back and forth, not entirely sure about what is and isn’t accurate about my relationship with empathy.

Therefore it wouldn’t be inaccurate to say I struggle with empathy. Just not in the ways you would expect. Sometimes I find it hard to connect but other times I struggle with how much I connect.

I’ve always felt I was empathetic, but that was more for situations where I could intellectualise it straight away. If a friend talked about their problems and feelings I would personally take on their problems. Perhaps more a people-pleasing tendency than an empathetic one.

I never thought I could walk into a room and intuitively pick up on what people were feeling. I always thought that it was my own anxiety and overthinking getting in the way. Because how is one supposed to comprehend another human beings emotional experience while simultaneously being able to comprehend their own?

From my observations of myself and society, there are things in life we can understand but not comprehend.

I can understand space being infinite nothingness that is continuously expanding but I can’t comprehend it.

If you’re reading this blog and are neurotypical, not AuDHD or just don’t relate to my experiences, I will say this; you don’t have to even begin to comprehend what it’s like to have my brain (or anyone else’s for that matter) but it would very much be appreciated if you would understand that it is my experience.

I think people conflate understanding and comprehension. They get caught up in their inability to comprehend that they forget, or simply don’t care, to understand. In my observations, I’ve found society places a lot of value on one’s ability to comprehend, as if comprehension is the deciding factor about what is truth and what isn’t. Your lack of comprehension is not my problem and it shouldn’t be yours either. If you can’t comprehend something. That’s fine. Find a place for understanding.

You can’t comprehend my neurodivergent brain? Try understanding it.

You can’t understand it? Try understanding that our brains are different.

You can’t understand our brains are different? Try understanding your own brain.

You can’t understand your own brain? Try accepting your brain.

That’s what I’m doing. I can’t completely comprehend or understand my own empathetic experiences. But, as hard as it may seem, I can accept that I don’t understand them.

Because who knows, maybe I could be completely wrong. Maybe there are no mosquitos. Or maybe there are, and they just never bite. I’ll never know.

But I do know this; I know that I care.

A lot.

This definitely speaks to me.

It is always a pleasure to hear that my words resonate with others! Especially since this post was quite difficult for me to articulate. Thank you!!

Thanks for this Collin. Our grandson (nearly 18 years old) has just been diagnosed with ASD. One of the things commented on in the report was his lack of empathy and ability to acknowledge emotions in either himself or others. Your words resonate so strongly. Thank you 😊

Thank you so much Andrea! A diagnosis can be difficult to navigate but can also be very rewarding! I wish your grandson the best on his journey as he continues to discover his own brain style outside of the assessment process!